What is a Bitcoin Private Key?

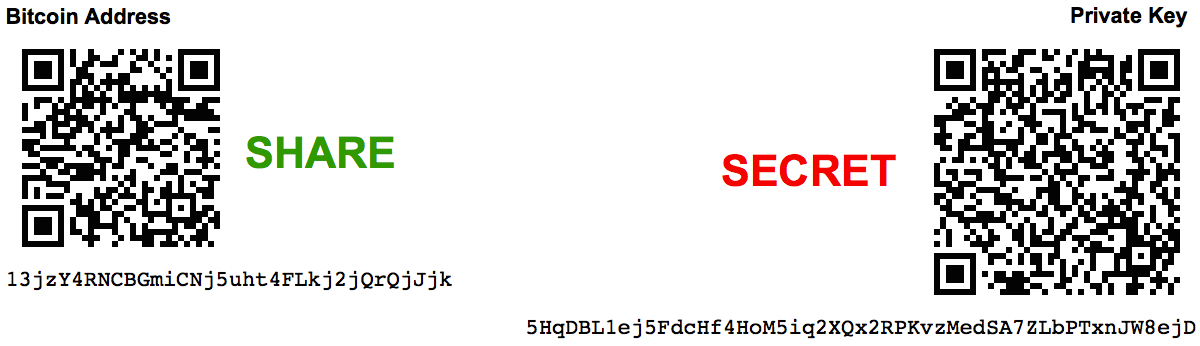

Simply put, a Bitcoin private key is the secret digital code which allows bitcoins to be spent. The following image of a Bitcoin wallet, generated at Bitaddress.org, shows both the address (13jzY…jJjk) for receiving funds and the associated private key (5HqD…8ejD) for spending funds:

The security of any Bitcoin wallet depends on the confidentiality of its associated private key(s). An attacker who learns your private key can steal your bitcoins! A Bloomberg TV host, Matt Miller, learnt this lesson the hard way when he revealed his private key on live television. Miller was promptly relieved of his wallet’s contents by a Bitcoin-savvy viewer (who later offered to return the funds).

- Public and Private Keys

- Public-Key Cryptography

- Bitcoin Private Keys and Public Addresses

- Technical Details

- Creating a Secure Private Key

- Private Key Generation Methods

Public and Private Keys

Your Bitcoin address, that long string of alphanumeric soup starting with a 1 (or 3), is meant for sharing. If Matt had revealed his public address (more properly known as a “Bitcoin address”) on air, viewers might have copied it down and sent him bitcoins - but that’s all. Matt goofed by revealing both the address and private key of his paper wallet, putting the balance up for grabs just as surely as if he’d revealed his bank details and passwords. Newcomers needn’t worry about accidentally exposing their private keys however; Bitcoin wallets won’t display them during the normal course of operations.

Public-Key Cryptography

If this sounds like a tough topic, don’t worry. By understanding the difference between Bitcoin addresses and private keys, you already have the gist of it. Satoshi Nakomoto drew on various cryptographic methods in the creation of Bitcoin; hash functions for proof-of-work mining and public key cryptography for public yet secure accounts.

Public-key cryptography was perfected in the mid 70’s and released as open source software by Phil Zimmermann in 1991 (despite the objections of the US government). Asymmetric or public-key cryptography begins with the creation of a seed which is used to create the private key, from which the public key is generated in a “one-way” mathematical process. It’s fiendishly difficult to reverse-engineer the public key in order to produce the private key. Hence, public keys may be securely published.

To send a secret message, the public key is used to encrypt plaintext such that it may only be decrypted by whoever holds the private key. The private key’s owner may also use it to digitally sign a message, which guarantees its authenticity.

Bitcoin Private Keys and Public Addresses

In Bitcoin, asymmetric cryptography secures transactions and accounts instead of messages. When the ownership of some amount of bitcoins is transferred to a new address, the wallet software creates an automatic digital signature to authorise that transaction. Note that at no time are bitcoins sent as files or messages to the new address; rather the change in ownership is broadcast to the entire network then, if valid, it’s recorded by miners into the blockchain. The blockchain is a continuously-updated public record of addresses and their associated balances… and only private keys grant access to those addresses.

It’s even possible to sign a message using a Bitcoin wallet’s private key or verify that message using the address. This is useful to prove ownership of a certain address and the coins contained therein. This video demonstrates the process (but beware the sites shown; online wallets are considered risky for storing bitcoins and brainwallet.org is a bad idea for reasons described below).

Technical Details

Bitcoin uses a 256 bit private key to generate a public key via ECDSA (Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm). This public key is then hashed to produce the Bitcoin address. This website provides a neat interactive overview of the entire process. While Bitcoin can be used without understanding the complex mathematics backing it, the more you learn the more confidence you’ll gain in the system. For example, the odds of two people generating the same private key are roughly 1 in 115 quattuorvigintillion.

Creating a Secure Private Key

Note that while you can manually generate a private key, as in the above-mentioned site’s text field, it’s unsafe to use anything but truly random input. New users should leave this step to their Bitcoin wallet, as the hash of some easily-memorised password is virtually guaranteed to be cracked. It’s possible to manually input random information, through such methods as rolling dice, but this is never a quick or straight-forward process.

To ensure the legitimacy of wallet (or any other) software you download, it’s worth learning how to use GnuPG, or similar public-key encryption tools, to verify its signature. For example, the current version of Bitcoin Core is signed by Wladimir J. van der Laan and if even the smallest code change is made, his signature would no longer match. This is the best way to ensure wallet software on a website has not been sneakily substituted for a malicious version which generates bad private keys.

Private keys generated via a website require full trust in the site’s honesty and information security practices. It should go without saying that this is not the recommended method. Many such sites use JavaScript to generate the private key on the client side but this method is not considered sufficiently secure for managing any significant amount of bitcoins. Generation of private keys via smartphone has proven problematic in the past due to a not-so-random random number generator, so such keys should not be used to secure significant amounts.

The most secure way to generate and store a private key is on offline hardware, like an air-gapped computer or custom-purpose device such as a TREZOR or Ledger.

Private Key Generation Methods

Bitcoin Core (formerly Bitcoin QT) uses randomly generated keys. It initialises with a pool of 100 randomly generated keypairs, a term used to describe the combination of an address and its private key. This limited pool of 100 keypairs leads to a problem… Bitcoin experts recommend, for privacy reasons, the generation of a new address every time a payment is requested. Such new addresses are drawn from the pool. After you’ve generated over 100 addresses, it quickly becomes a chore to maintain a perfect backup record. Should you receive a million bitcoins via your 101st address, suffer a catastrophic hard drive failure and then discover you failed to properly back up the private keys… cue the “and it’s gone” meme.

This problem is solved by Bitcoin Improvement Proposal (BIP) 32 and implemented in Hierarchical Deterministic (HD) Bitcoin wallets, such as Electrum, Mycelium and MultiBit. HD wallets use an algorithm to generate a practically infinite number of addresses from a single seed. This eliminates the tedious necessity of on-going backup procedures. Another advantage of HD wallets is that you may generate further receive-only addresses without using your original seed. You need only access your private key when you wish to spend from these addresses. Yet another advantage is that certain HD wallets, such as Electrum, generate the private key’s seed as a sequence of twelve or twenty-four common words. This makes memorisation or transcription errors far less likely.

Brain wallets are generated by hashing a user input. Generally speaking, anything memorable is easy to break. Crackers have comprehensive lists of common password combinations, words, phrases, lyrics, quotes, etc. in all known languages (including Klingon) which they run through cracking software capable of 1000s of guesses per second on a basic PC. To reiterate, brain wallets are a bad idea.

Categories