What is Bitcoin Mining?

If “mining” sounds like a process which extracts value from Bitcoin, nothing could be further from the truth! Miners are the backbone of the Bitcoin network. Without miners, the network would collapse and lose all value. The role of miners is to secure the network and to process every Bitcoin transaction. Miners achieve this by solving a computational problem which allows them to chain together blocks of transactions (hence Bitcoin’s famous “blockchain”). For this service, miners are rewarded with newly-created Bitcoins and transaction fees.

- The Blockchain

- Isn’t Mining a Waste of Electricity?

- The Mining Process

- Mining Difficulty

- Block Reward Halving

- Honest Miner Majority Secures the Network

- Mining Hardware

- Mining Pools

- Mining Centralization

The Blockchain

To understand mining, it’s first necessary to understand the Bitcoin blockchain. All Bitcoin transactions are recorded in the blockchain, in a linear, time-stamped series of bundled transactions known as blocks. The blockchain is essentially a public ledger, which is freely shared, continually updated and under no central control.

Isn’t Mining a Waste of Electricity?

Certain orthodox economists have criticized mining as wasteful. It must be kept in mind however that this electricity is expended on useful work: enabling a monetary network worth billions (and potentially trillions) of dollars! Compared to the carbon emissions from just the cars of PayPal’s employees as they commute to work, Bitcoin’s environmental impact is negligible. As Bitcoin could easily replace PayPal, credit card companies, banks and the bureaucrats who regulate them all, it begs the question: isn’t traditional finance a waste? Not just of electricity, but of money, time and human resources!

The Mining Process

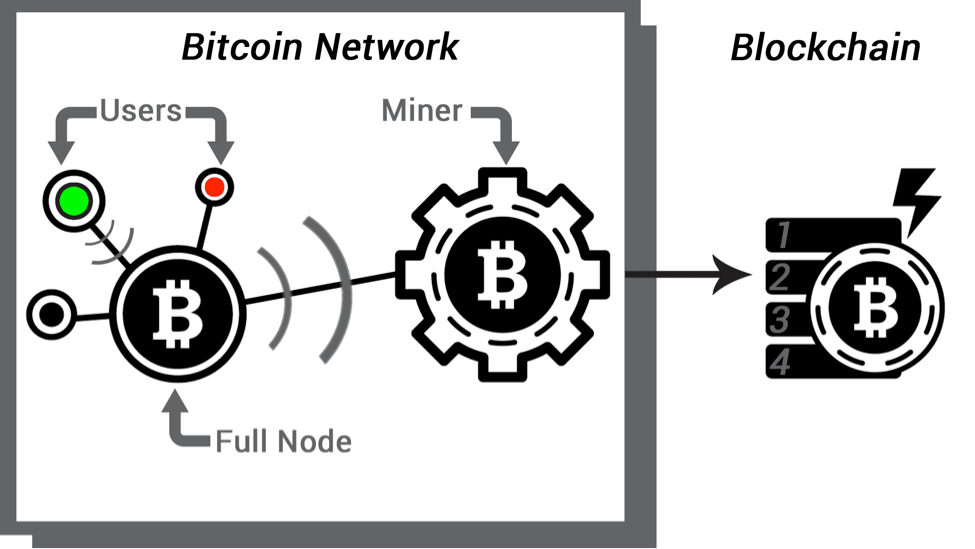

This simplified illustration is helpful to explanation:

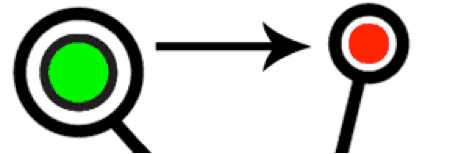

1) Spending

Let’s say the Green user wants to buy some goods from the Red user. Green sends 1 bitcoin to Red.

2) Announcement

Green’s wallet announces a 1 bitcoin payment to Red’s wallet. This information, known as transaction (and sometimes abbreviated as “tx”) is broadcast to as many Full Nodes as connect with Green’s wallet - typically 8. A full node is a special, transaction-relaying wallet which maintains a current copy of the entire blockchain.

3) Propagation

Full Nodes then check Green’s spend against other pending transactions. If there are no conflicts (e.g. Green didn’t try to cheat by sending the exact same coins to Red and a third user), full nodes broadcast the transaction across the Bitcoin network. At this point, the transaction has not yet entered the Blockchain. Red would be taking a big risk by sending any goods to Green before the transaction is confirmed. So how do transactions get confirmed? This is where Miners enter the picture.

4) Processing by Miners

Miners, like full nodes, maintain a complete copy of the blockchain and monitor the network for newly-announced transactions. Green’s transaction may in fact reach a miner directly, without being relayed through a full node. In either case, a miner then performs work in an attempt to fit all new, valid transactions into the current block.

Miners race each other to complete the work, which is to “package” the current block so that it’s acceptable to the rest of the network. Acceptable blocks include a solution to a Proof of Work computational problem, known as a hash. The more computing power a miner controls, the higher their hashrate and the greater their odds of solving the current block.

But why do miners invest in expensive computing hardware and race each other to solve blocks? Because, as a reward for verifying and recording everyone’s transactions, miners receive a substantial Bitcoin reward for every solved block!

And what is a hash? Well, try entering all the characters in the above paragraph into this hashing utility. If you pasted correctly - as a string hash with no spaces after the exclamation mark - the SHA-256 algorithm used in Bitcoin should produce: “6afc21238f2d33e24e168195888721dd5ace05d76196671d6739789af92201ed.” If the characters are altered even slightly, the result won’t match. So, a hash is a way to verify any amount of data is accurate. To solve a block, miners modify non-transaction data in the current block such that their hash result begins with a certain number (according to the current Difficulty, covered below) of zeroes. If you manually modify the string until you get a 0… result, you’ll soon see why this is considered “Proof of Work!”

5) Blockchain Confirmation

The first miner to solve the block containing Green’s payment to Red announces the newly-solved block to the network. If other full nodes agree the block is valid, the new block is added to the blockchain and the entire process begins afresh. Once recorded in the blockchain, Green’s payment goes from pending to confirmed status.

Red may now consider sending the goods to Green. However, the more new blocks are layered atop the one containing Green’s payment, the harder to reverse that transaction becomes. For significant sums of money, it’s recommended to wait for at least 6 confirmations. Given new blocks are produced on average every ten minutes; the wait shouldn’t take much longer than an hour.

The Longest Valid Chain

You may have heard that Bitcoin transactions are irreversible, so why is it advised to await several confirmations? The answer is somewhat complex and requires a solid understanding of the above mining process.

Let’s imagine two miners, A in China and B in Iceland, who solve the current block at roughly the same time. A’s block (A1) propagates through the internet from Beijing, reaching nodes in the East. B’s block (B1) is first to reach nodes in the West. There are now two competing versions of the blockchain!

Which blockchain prevails? Quite simply, the longest valid chain becomes the official version of events. So, let’s say the next miner to solve a block adds it to B’s chain, creating B2. If B2 propagates across the entire network before A2 is found, then B’s chain is the clear winner. A loses his mining reward and fees, which only exist on the invalidated A-chain.

Going back to the example of Green’s payment to Red, let’s say this transaction was included by A but rejected by B, who demands a higher fee than was included by Green. If B’s chain wins then Green’s transaction won’t appear in the B chain - it will be as if the funds never left Green’s wallet.

Although such blockchain splits are rare, they’re a credible risk. The more confirmations have passed, the safer a transaction is considered.

Mining Difficulty

If only 21 million Bitcoins will ever be created, why has the issuance of Bitcoin not accelerated with the rising power of mining hardware? Issuance is regulated by Difficulty, an algorithm which adjusts the difficulty of the Proof of Work problem in accordance with how quickly blocks are solved within a certain timeframe. Difficulty rises and falls with deployed hashing power to keep the average time between blocks to around 10 minutes.

Block Reward Halving

Satoshi designed Bitcoin such that the block reward, which miners automatically receive for solving a block, is halved every 210,000 blocks. As Bitcoin’s price has risen (and is expected to continue to rise over time) substantially, mining remains a profitable endeavour despite the falling block reward… at least for those miners on the bleeding edge of mining hardware with access to low-cost electricity.

Honest Miner Majority Secures the Network

To successfully attack the Bitcoin network by creating blocks with a falsified transaction record, a dishonest miner would require the majority of mining power so as to maintain the longest chain. This is known as a 51% attack and it allows an attacker to spend the same coins multiple times and to blockade the transactions of other users at will. To achieve it, an attacker needs to own mining hardware than all other honest miners. This imposes a high monetary cost on any such attack.

At this stage of Bitcoin’s development, it’s likely that only major corporations or states would be able to meet this expense… although it’s unclear what net benefit, if any, such actors would gain from degrading or destroying Bitcoin.

Mining Hardware

When Satoshi released Bitcoin, he intended it to be mined on computer CPUs. However, enterprising coders soon discovered they could get more hashing power from graphic cards and wrote mining software to allow this. GPUs were surpassed in turn by ASICs (Application Specific Integrated Circuits). Nowadays all serious Bitcoin mining is performed on ASICs, usually in thermally-regulated data-centres with access to low-cost electricity. Economies of scale have thus led to the concentration of mining power into fewer hands than originally intended.

Mining Pools

As with GPU and ASIC mining, Satoshi apparently failed to anticipate the emergence of mining pools. Pools are groups of cooperating miners who agree to share block rewards in proportion to their contributed mining power. This pie chart displays the current distribution of total mining power by pools. While pools are desirable to the average miner as they smooth out rewards and make them more predictable, they unfortunately concentrate power to the mining pool’s owner.

Mining Centralization

Pools and specialised hardware has unfortunately led to a centralization trend in Bitcoin mining. Core developer Greg Maxwell has stated that, to Bitcoin’s likely detriment, a handful of entities control the vast majority of hashing power. It is also widely-known that at least 50% of mining hardware is located within China.

However, it’s may be argued that it’s contrary to the long-term economic interests of any miner to attempt such an attack. The resultant fall in Bitcoin’s credibility would dramatically reduce its exchange rate, undermining the value of the miner’s hardware investment and their held coins. As the community could then decide to reject the dishonest chain and revert to the last honest block, a 51% attack probably offers a poor risk-reward ratio to miners.

Bitcoin mining is certainly not perfect but possible improvements are always being suggested and considered.

Categories